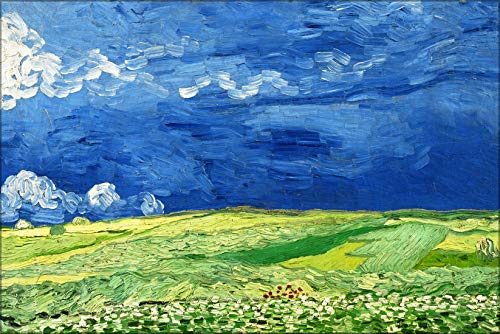

Thunderstorms are as much a part of summer as snow is to winter. Across most of North America, a spark of lightning on the horizon and a low rumble of thunder are common in the afternoon from early June through mid‑September. It is not unusual for thunderstorms to produce violent gusts of wind, heavy downpours of rain and occasionally severe temperature changes. Even microbursts and tornadoes, though dreaded, are an accepted part of the weather mix each summer. But hail is almost always a surprise.

Perhaps because they are so rare, occurring less than once a decade in most places, severe hailstorms ‑‑ the kind that produce hail the size of golf balls or larger ‑‑ are almost always unexpected, unpredicted and devastating.

The potential for hail exists in most of those high‑rise clouds that look like smoke rising from the top of a volcano. Rain in the upper reaches of these clouds sometimes gets caught in an updraft and rises instead of falls. As it goes up it freezes, forming little pellets of ice. When little pellets of ice fall to earth, they are called graupel or snow pellets. Not until they reach 5 millimeters, or about the width of a dime, are they officially classified as "hail."

To get that big, the ice pellets in a storm cloud must fall and then be lifted by an updraft several times. The stronger the updraft, the larger the hail can grow. It takes an updraft of more than 55 miles per hour to create hail the size of a golf ball, and an updraft of 90 miles per hour or more to generate hail the size of a baseball.

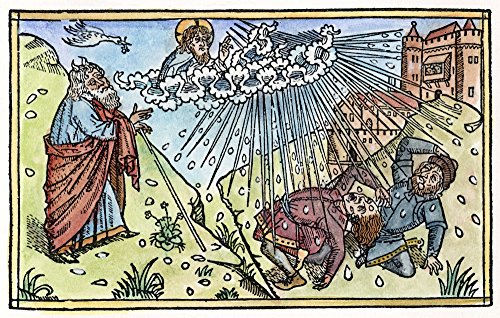

Hail that big can be deadly.

A 1985 hailstorm in Cheyenne, Wyoming, killed a dozen residents with baseball‑size hail and left another 70 injured. A year later, at least 100 people died during a hailstorm in China's Sichuan province.

Whatever its size, when hail comes down from the heavens it usually falls as a "hailstreak," blanketing an area a half‑mile wide and up to five miles long. Step a couple feet outside this streak in any direction and there may be no hail at all.

During the dozen years I lived along the northern edge of the Great Basin in Idaho there were several showers of ice pellets but only two real hailstorms. The first leveled our garden but left the rows of corn and carefully staked tomatoes of our neighbor across the street unscathed. A second hailstreak was less discriminating. It arrived on a dark, swirling wall cloud that dipped down from the thundercloud above and turned to sheets of iceballs as it touched the ground.

In most farming districts, hail is the most feared of all weather phenomena. Even hail of small diameters with strong winds are sufficient to damage crops. Small hail with strong winds can pierce crops such as lettuce and cabbage. Larger hail can damage crops even with lighter winds.

The storm that passed our way made a terrible mess of our strawberry beds, stripped leaves off trees, totaled our apple crop, topped onions, minced mesclun, shattered the glass on one cold frame and pierced the tender cucumber plants inside. Seedlings that weren't shredded by the hail were frostbitten by the three‑inch thick layer of ice that took more than an hour to melt. Our home and animals came through unscathed, but the roof and hood of our car collected about 40 quarter‑size dents.

Surveying the damage and bemoaning my losses, one thought kept recurring in my mind: I forgot about hail.