This time it was an oddly-striped finch that caught my attention, perched on the feeder outside my office window. The bird has thick bands of orange on either side of his pecan-sized head and looks like he is wearing one of those tear-shaped fiberglass bicycle helmets.

Never mind the dozens of goldfinches fluttering about or the bold crowns of the Pine Siskin, it is the odd bird, the rarely-seen-in-these-parts critter that gets the most notice. It is this uncommon sight that gives me pause.

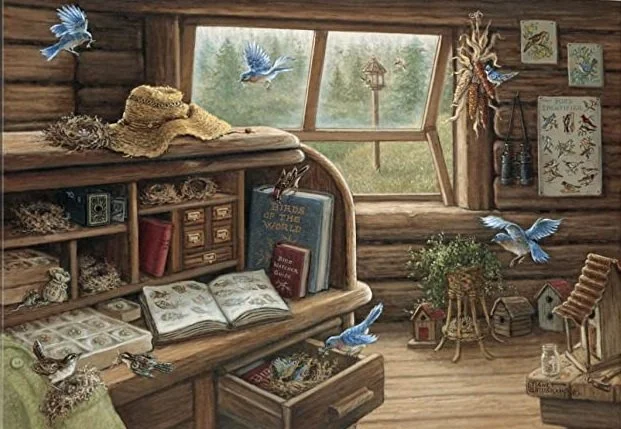

Isn't that the way it is with birdwatching? It's not the everyday bird that draws enthusiasts to bogs and barrens with their binoculars and field guides.

More than 60 million Americans feed and watch birds. Many do this in their backyards, but many are willing to travel great distances and endure physical discomfort to participate in the activity called "birdwatching." Recently ranked with other American recreations, birdwatching placed second ahead of gardening.

It's difficult to explain the appeal of birding. It's one of those things you've got to do to understand. But retired Stanford professor Leonard Nathan has devoted a book to his obsessive need to justify his pursuit of the elusive Snow Bunting as much more than dry ornithological research and different from a hunter pursuing his prey.

Nathan argues in "Diary of a Left-Handed Birdwatcher" that a sense of epiphany, or a "shock of recognition," occurs when an intense birdwatcher is surprised by the sudden presence of a rare species.

"Why are watchers reluctant to lower their binoculars?" he asks. "To make sure of the identity of the bird, yes, but also from a strong desire to prolong so special a seeing, not the consummation of the hunt, but the experience of knowledge. The meaning and mystery of otherness."

Like fly fishing or listening to great music, birdwatching can carry a person away from day-to-day concerns and into another realm of being.

"The only motion: three Great Egrets gliding by in their hunched flight. I have seen egrets too many times to count, but these seem utterly fresh and vivid," Nathan writes of one watch. "It's like an ink drawing except that I'm in it. And in it, I require nothing else but to be in it. Now a thrush sings its upward-circling quaver, and what seemed perfect before seems more so now. And then a human voice calls from somewhere behind me, and I am fetched, unwillingly, back to the other world."

I'm no birdwatcher, but I do notice birds, especially late in winter when so much is still and cold and hibernating. But when I saw that bird with orange lores, I stood still and pondered it wordlessly. For a brief moment, my observation was a form of communion with creation, a prayer.

We all have such moments. For some, it's sunsets or thunderstorms. For others, it's waves crashing on a beach. Birdwatchers chase after these moments, one bird at a time.