In an effort to probe the extent to which this curious phenomenon of “verbal mimesis” among critics might be merely that other kind of coincidence—just chance—I turn to the evidence culled from two of the best twenty-first-century literary biographers in the profession: Rosemarie Bodenheimer and Robert Douglas-Fairhurst.

Measuring the varying levels of bodily idiom usage in the cases of these two biographers may provide the best test cases yet for several reasons. First, both Bodenheimer and Douglas-Fairhurst have produced major, full-length literary biographies of Dickens and of another Victorian author: Bodenheimer has written one book on George Eliot and another on Dickens; Douglas-Fairhurst one on Dickens and one on Lewis Carroll.

…

In The Real Life of Mary Ann Evans, Bodenheimer (1994) uses a total of just eleven body idioms in 267 pages (120,100 words). In Knowing Dickens (2007), she uses 119 body idioms in 208 pages (98,100 words). Even without adjusting for word length, Bodenheimer uses over ten times the body idioms when writing about Dickens than she does when writing about Eliot.

The proportional case with Douglas-Fairhurst is only slightly less astounding. In Becoming Dickens (2011), he uses 264 body idioms in 336 pages (133,700 words). In The Story of Alice (2015), he uses only thirty-nine body idioms in 415 pages (164,300 words).

These lopsided proportions, combined with what we know about Dickens as far and away the highest user of body idioms among nineteenth-century novelists, make it very likely that there is some kind of Pouletian “coincidence” between the mind of the critic and the mind of the author. Put another way, Dickens’s body idioms are contagious: they have a strong tendency to subdue the critic’s nature to the stuff it works in, like the dyer’s hand.

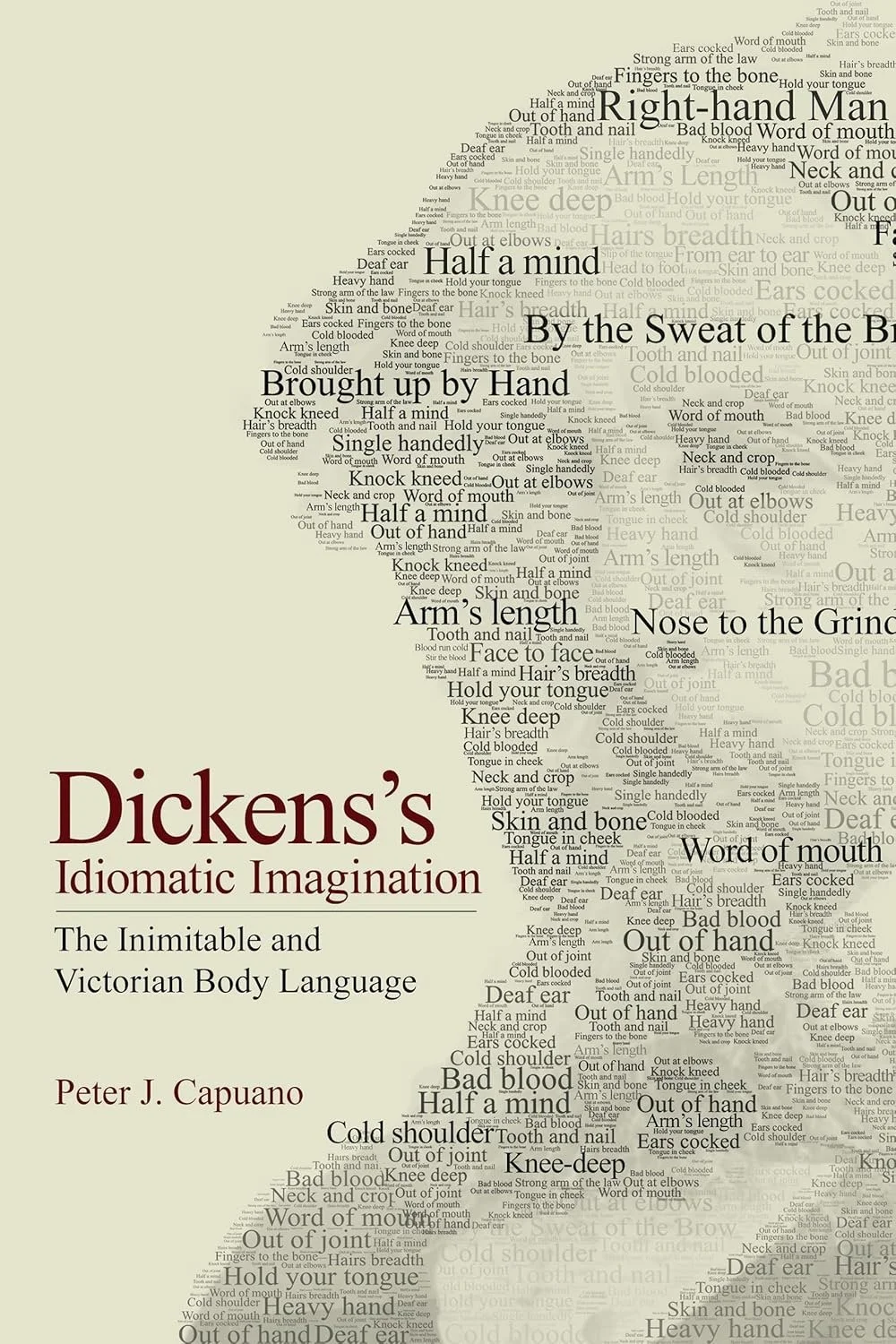

Throughout this book, I have referred to Dickens as the “Inimitable,” and yet, paradoxically, the sharpest register of his genius turns out to be its absorptive influence, carried across to produce lexical imitation in his critics. Like no other Victorian author, we speak of Dickens using the vernacular language that his novels have put within our earshot, the idioms he has pressed into currency by putting them in our mouths and at the ends of our fingertips. Ultimately, what could be more inimitable?