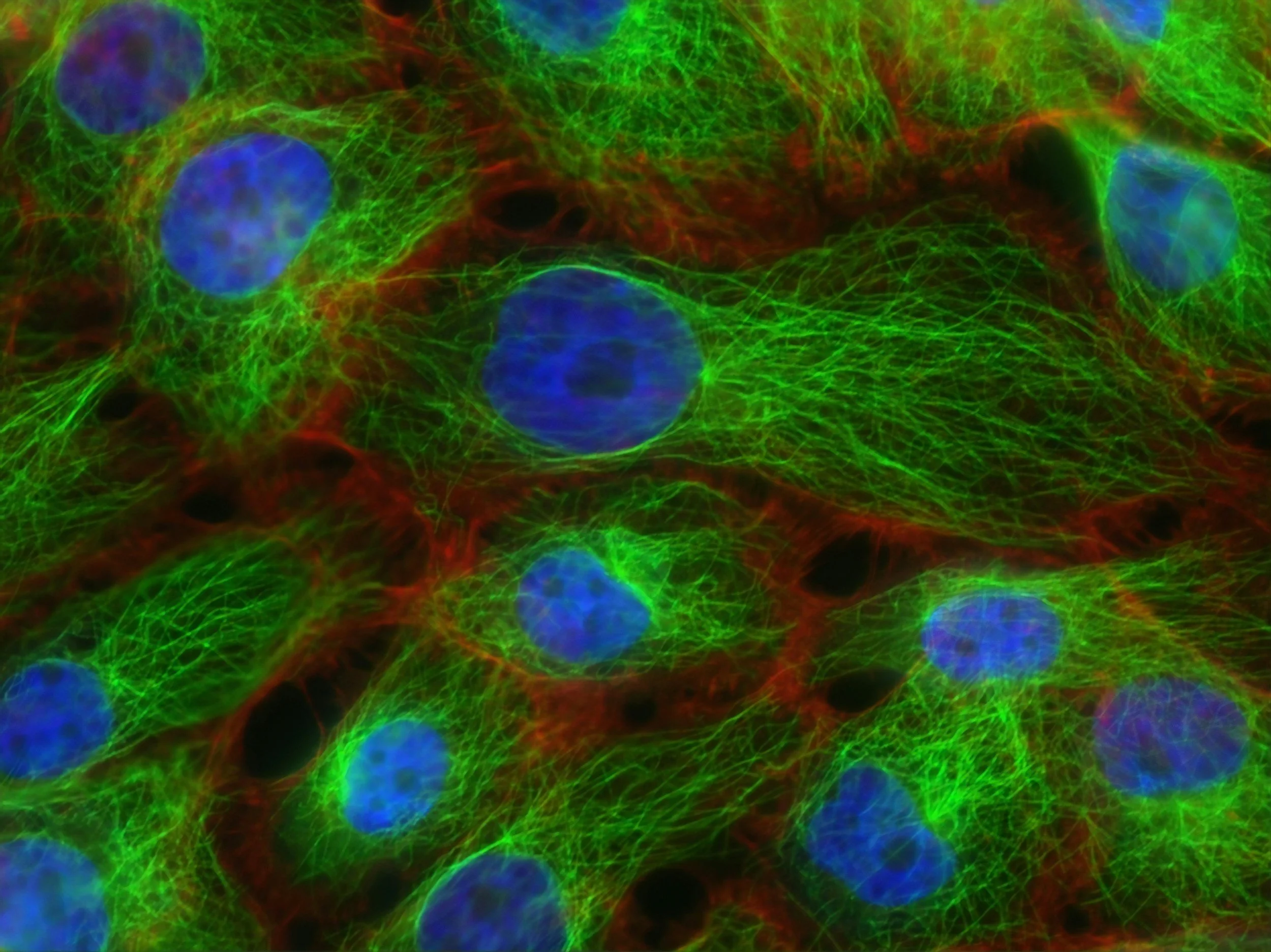

Photo by National Cancer Institute on unsplash

The Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of Earth’s living organisms lived about 4.5 billion years ago, according to a study by biologists at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research.

Tara Mahendrarajah and senior author Anja Spang, with collaborating partners from Universities in Bristol, Hungary and Tokyo, published their findings in Nature Communications.

What LUCA looked like is unknown, but it must have been a cell with ribosomal proteins and an ATP synthase.

"These proteins are shared by all bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes such as plants and animals," Spang said.

Using a new molecular dating approach, the researchers were able to estimate the moment when LUCA split into bacteria and archaea, as well as when eukaryotes emerged.

Dating the root

This new dating of the primordial form of all life is not dramatically different from previous estimates.

“Dating gets increasingly uncertain towards the root of the tree of life,” co-corresponding author Tom Williams of the University of Bristol explains. One of the real surprises of this research by Mahendrarajah and colleagues are further up the tree of life. "Archaea are often called ancient bacteria," says Spang.

"That would suggest that they stem from an ancestor that is older than the one of today's bacteria. But with this improved dating approach, we see that the ancestor of all current archaea lived between 3.37 and 3.95 billion years ago. This makes the last common ancestor of known archaea younger than the one of all bacteria, which lived between 4.05 and 4.49 billion years back. This suggests that earlier archaea either died out, or they live somewhere hidden on Earth where we have not found them yet,” Spang hypothesizes.

We are fusions

The eukaryotes, meaning cells with a nucleus, such as all plants and animals, had their last common ancestor between 1.84 to 1.93 billion years back.

Tara Mahendrarajah explains: "If you imagine all life on earth as a family tree, LUCA is at the base and at some point, the trunk splits into a bacterial and an archaeal branch. But eukaryotes are not a separate branch on this tree of life, but rather a fusion of two branches that came out of the bacterial and the archaeal branches. We have a bit of both in us.”

Understanding natural history

“Our new estimates for the age of the archaeal and bacterial ancestors of eukaryotes will help to improve our models on eukaryotic origins,” Edmund Moody of the University of Bristol adds. “This new way of viewing the tree of life helps us track how cells have evolved over time on Earth. It also gives us a foundation to figure out what those early microbes did in their old environments and how their evolution is linked to natural history.”

Spang further points out: “Insights into the role of both ancient and extant microbes in nutrient cycling can help to better understand and predict future biodiversification in a changing environment, including climate warming.”