Humans Hunted Woolly Mammoths Into Extinction... Or Did They?

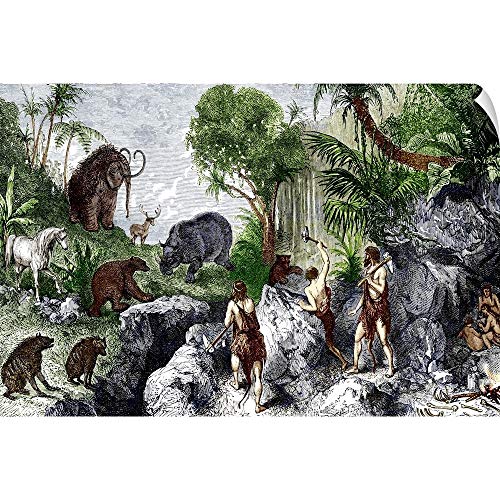

Woolly mammoths, giant armadillos and three species of camel were among more than 30 mammals that were hunted to extinction by North American humans 13,000 to 12,000 years ago, according to a sophisticated computer model. John Alroy, a researcher with the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) at UC Santa Barbara, performed the modeling. NCEAS houses the best ecosystem computer modeling capacity available in the world, according to Alroy.

"This was a big event in North America," he said. "And, although humans were responsible for the extinctions, it wasn't clear to them because it happened over a 1,000-year period. It took so long that they didn't realize it until it was too late."

Earlier computer simulations of the timeline were too simple to grasp the total picture of extinctions, according to Alroy. He said the current model is a conservative one that is quite robust to criticism.

"More than half of the large mammal biota of the Americas disappeared in a cataclysmic extinction wave at the very end of the Pleistocene," Alroy concluded in an article in Science. Some of the mammals that became extinct were: woolly mammoths; Columbian mammoths; American mastodons; three types of ground sloths; giant armadillos; several species of horses; four species of pronghorn antelopes; and three species of camels.

But why did some species of large mammals become extinct and others not? Moose, Canadian elk, and bison survived. "These had a broader distribution," explained Alroy. They were able to move into what is now Canada as the glaciers melted.

“These animals may also have developed more ways to avoid humans since they co-evolved with humans here, in Europe and Asia,” he said.

Sources: University of California, Santa Barbara; University of Washington

Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids by Jordi Agusti, Mauricio Anton

Beyond the Dinosaurs! : Sky Dragons, Sea Monsters, Mega-Mammals, and Other Prehistoric Beasts

The Anthropology of Climate Change: An Historical Reader by Michael R. Dove

Mama Poc: An Ecologist's Account of the Extinction of a Species

The Fate Of The Mammoth: Fossils, Myth, And History By Claudine Cohen The University Of Chicago Press, 2002

No... Climate Change Killed Off the Mammoths

A University of Washington archaeologist disputes the so-called overkill hypothesis that pins the crime on the New World's first humans.

"While the initial presentation of the overkill hypothesis was good and productive science, it has now become something more akin to a faith-based policy statement than to a scientific statement about the past," said Donald Grayson, a UW anthropology professor

Writing in the Journal of World Prehistory, Grayson said there are dangerous environmental implications of using overkill hypothesis as the basis for introducing exotic mammals into arid western North America. He looks askance at the idea of introducing modern elephants, camels and other large herbivores into the southwest United States.

"Overkill proponents have argued that these animals would still be around if people hadn't killed them and that ecological niches still exist for them. Those niches do not exist. Otherwise the herbivores would still be there."

If early humans didn't kill North America's megafauna, then what did?

Grayson points to climate shifts, during the late Pleistocene epoch, which ended about 10,000 years ago, and subsequent changes in weather and plants as the likely culprits in the demise of North America's megafauna. The massive ice sheets that covered much of the Northern Hemisphere began retreating. In North America, this icy mantle prevented Arctic weather systems from extending into the mid-continent. Seasonal weather swings were less dramatic and didn't reach as far south as they presently do. But with this change, the climate became more similar to today's, marked by cold winters and warm summers.

As a result, an unusual patchwork aggregation of plant communities ceased to exit and there was a massive reorganization of biotic communities. At the same time, new data developed by Russell Graham, a paleontologist with the Denver Museum, shows that small mammals such as shrews and voles were moving about the landscape and becoming locally extinct. And there were the extinctions of some 35 genera of large North American mammals, including horses, camels, bears, giant sloths, saber-toothed cats, mastodons and mammoths.

The overkill hypothesis was proposed by retired University of Arizona ecologist Paul Martin in 1967 and its basic arguments haven't changed since. It claims large mammal extinctions occurred 11,000 years ago; Clovis people were the first to enter North America, about 11,000 years ago; Clovis people were hunters who preyed on a diverse set of now-extinct large mammals; records from islands show that human colonists cause extinction; therefore, Clovis people caused extinctions.

"Martin's theory is glitzy, easy to understand and fits with our image of ourselves as all-powerful," said Grayson "It also fits well with the modern Green movement and the Judeo-Christian view of our place in the world. But there is no reason to believe that the early peoples of North America did what Martin's argument says they did."

First of all there is no compelling evidence that the majority of the extinctions occurred during Clovis times, said Grayson. Only 15 genera can be shown to have survived beyond 12,000 years ago and into Clovis times. For 30 years, overkill proponents have assumed that since some genera can be shown to have become extinct around 11,000 years ago, all the big North American mammals became extinct at that time, he said.

"That's an enormous assumption, even though there is no compelling evidence of it in North America," Grayson said.

He also said overkill proponents have consistently ignored the possibility that the Clovis people were not the first humans in the New World. They reject evidence from a site in Monte Verde, Chile, showing human occupation that dates some 12,500 to 12,800 years ago. Monte Verde also has yielded some material that may push human occupation back to 33,000 years before the present.

Well-accepted Clovis sites dating between 10,800 and 11,300 years ago have been found in North America, and distinctive, fluted projectile points mark this culture. Clovis artifacts have been found with mammoth remains in more than a dozen sites across the Great Plains and the southwestern United States.

Grayson said there is no reason to doubt that these people scavenged and hunted large mammals. But he cautioned that while mammoths, mastodons, horses and camels were the most common large mammals in the late Pleistocene - 10,000 to 20,000 years ago - only mammoths are found at kill sites associated with Clovis people.

As for the claim that human colonization of the world's islands resulted in widespread vertebrate extinction, Grayson said this did not occur simply because of human hunting.

"No one has ever securely documented the prehistoric extinction of any vertebrate as a result human predation, though it may certainly have happened. In virtually all cases, when people colonize an area many other changes follow - fire, erosion and the introduction of a wide range of predators and competitors.

"We do know that human colonists caused extinctions in isolated, tightly bound island settings, but islands are fundamentally different from continents," he added. "The overkill hypothesis attempts to compare the incomparable and there is no evidence of human-caused environmental change in North America. But there is evidence of climate change. Overkill is bad science because it is immune to the empirical record."

For more information, contact Grayson at (206) 543-5587.