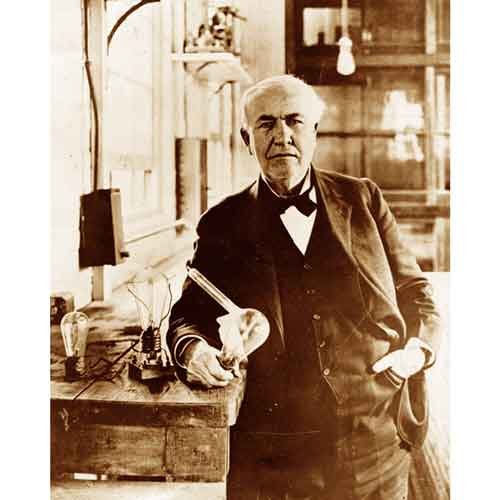

It was as if someone flipped a giant switch, taking the whole world from darkness into light. It happened on New Year's Eve, 1879, and Thomas Edison was that someone.

Arguably the most important invention of the late 19th century, the incandescent light bulb was the catalyst for a nation’s transformation from a rural to an urban-dominated culture.

"On New Year's Eve, trainloads of sightseers arrived at Menlo Park to witness 'Edison's latest marvel,' his laboratory and grounds glowing with the light of about fifty of these incandescent bulbs," writes Ernest Freeberg in The Age of Edison.

"One Edison biographer described the event as a "spontaneous mass festival," as thousands pressed in to turn the light on and off themselves and to shake the great inventor's hand."

Newspaper journalists struggled to find words to describe the new light before them, so very different from candlelight, lanterns and gas lamps. "There is no flicker," one reported. "There is nothing between it and darkness. It consumes no air and, of course, does not vitiate any. It has no odor or color."

In the afterglow of Edison's invention, more than 600 companies emerged across the U.S. with a dozen rival lighting systems, all competing to bring electricity to cities and towns across America.

This electric "gold rush" had its casualties, as much of Boston's business district burned down in a fire caused by shoddy wiring and the mess of unregulated development led to electrical fires and electrocutions.

It took decades for the electric industry to consolidate into two major corporations, General Electric and Westinghouse, and even longer for national safety standards to be enforced.