by Michael Hofferber. Copyright © 1996 All rights reserved.

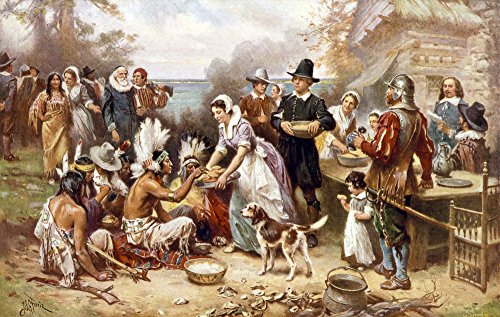

Thanksgiving did not begin with the Pilgrims who settled along the northeast coast of North America in 1620. Back in England, where they came from, a thanksgiving feast in November to celebrate completion of the harvest was a long-held tradition.

Nor was the concept of a thanksgiving feast new to the native Algonquin Indians who helped the struggling Pilgrim settlers adjust to the food sources of their new home. The Algonquins held at least five major thanksgiving festivals a year, beginning with a Maple Dance in late winter to celebrate when the sap began to run.

But when Captain Miles Standish, leader of the Pilgrims, invited the Algonquin leaders and their families to join his group for a Thanksgiving celebration something unique happened. The Pilgrims ran low on provisions and several Algonquins rushed home to fetch more food: five deer, several wild turkeys, fish, beans, squash, corn soup, corn bread and berries.

What began as a traditional Pilgrim thanksgiving became what was probably the first cross-cultural American pot luck and, consequently, the first true American Thanksgiving.

Some chefs and food writers say America has no cuisine, at least not in the same sense that Chinese, Italian, Mexican and Middle Eastern cuisine is recognized.

Americans are too busy and too preoccupied with other matters to take much interest in where their food comes from, how it is prepared or how it is eaten, claims food anthropologist Sidney W. Mintz in his book “Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom.”

“That they do not is a fact of great importance; it implies not only that they lack a cuisine, but also that they probably will never have one.”

Well... Mintz must have forgotten or overlooked Thanksgiving.

Yes, it is true that Americans eat out frequently and often choose fast foods or takeouts over the home-cooked meal. We eat a lot of prepared and packaged foods, as Mintz points out, and have diets high in animal protein, salt, fats and processed sugars. We drink more sodas than tap water and include too few fruits and vegetables in our diets. And, yes, we spend precious little time considering our food, neither preparing it nor discussing it nor having strong opinions on the subject... until Thanksgiving.

For about six weeks, from Thanksgiving until New Years, the American Cuisine is reaffirmed with fervor and excitement. Folks who haven’t cooked from scratch all year start basting turkeys and peeling potatoes and rolling out pie dough. The lost art of baking becomes an obsession and arguments are waged over stuffings and fillings and sauces and aperitifs.

Americans may be eclectic eaters all the rest of the year, but during the holiday season we come together beneath a common cuisine of turkey, pumpkin, corn, beans, squash, potatoes, tomatoes, cranberries, apples, chocolate and coffee.

No, you can’t find “American” meals the same way you locate fine French cuisine, East Indian cookery, or even a Vietnamese restaurant. And aside from the menu at McDonald’s, there are no distinctly American dishes served all over the world.

But if you live in or visit an American home, or if you attend a potluck dinner or banquet at some church or convention center over the holidays -- for it is only in the home or among a large group that this cuisine is prepared -- you will taste the essence of America, its indigenous food stuffs basted and baked and steamed and mashed by hands of all colors, faiths, ethnic origins and degrees of kitchen skill.