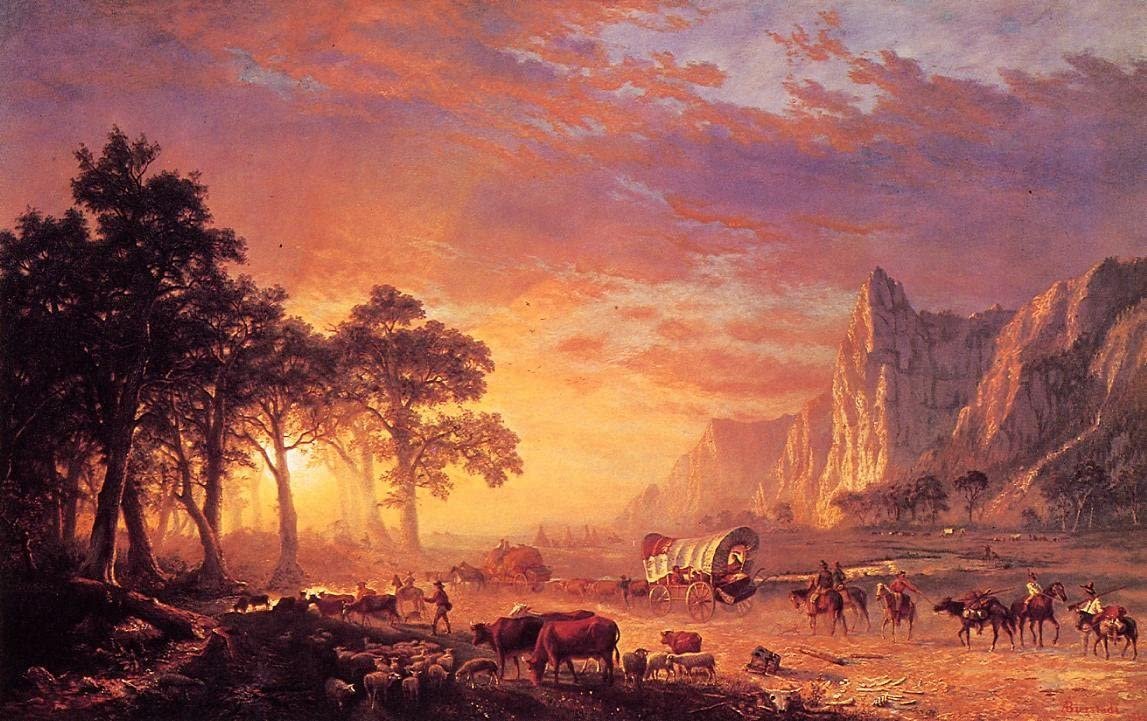

Over 175 years have passed since the first of some 300,000 emigrants started a massive migration across the heartland of North America to the continent's Pacific shores. Beginning in Independence, Missouri, and ending in Oregon City, Oregon, the "Oregon Trail" stretched for 2,000 miles across six states.

Tracks from this passage are still embedded in the Snake River Plain not far from here. I've walked in them several times, pressing my feet where wagon wheels and oxen and well-worn boots once tread, and it continues to astonish me that so many people would give up their homes back East and travel so far with so little assurance of a better life at the far end of their seven-month journey.

This was no pleasure cruise, nor a mere "Adventure in Moving," as U-Haul advertises its rental vans and trailers. The folks who followed the Oregon Trail met violent winds, quicksand, floods, buffalo stampedes, disease and Indian attacks. Nearly 10 percent, or roughly 30,000 of them, lost their lives on the trail. Of those that survived, many suffered the loss of livestock, personal fortunes and prized belongings.

What's also hard to fathom is the fact that precious little of the land that the survivors laid claim to at the end of their arduous journeys remains with their ancestors today.

Truth is, a great number of those who followed the Oregon Trail to Oregon did not stay. Promoters failed to mention the rain and swindlers and privations associated with homesteading. Some folks moved on to California. Others returned to the homes they left behind, throwing themselves at the mercy of their relatives and friends.

"Settlers" is an inaccurate description of most who made these journeys; "unsettled" is a fairer adjective and "backtrackers" is what others on the trail called them. Some used the trail three or four times, following their dreams back and forth, back and forth.

I've done some backtracking myself, having lived on both coasts and many states in between. And now I live in what's often referred to as a "backwash state," Idaho, populated largely by Californians and others looking for a better life or a second chance.

Backtracking is so common among Americans, in fact, that it's almost a cultural trait. Nearly a third of us will change residences in the next two years and many others will feel they should have. In every move, there's one overriding reason like a better job or bad neighbors or a longing to return to someplace familiar or a pining for someplace new.

We get tired of the old haunts, but once we've moved we miss them. We run from the provincialism of rural life only to be repulsed later by what we find in the city or suburb.

Like young Huck Finn, we fear being "sivilized" by Tom Sawyer's Aunt Sally and are determined to "light out for the Territory" if anyone starts making demands.

This is the urge that blazed the Oregon Trail, I believe. It prompted a goodly portion of 19th century Americans to leave their farms and friends and families for an uncertain future in the Territory. By its energy a continent was populated. Because of its endurance our souls remain unsettled.