Trying to imagine how my grandparents lived their lives is hard enough, but picturing Native Americans camping out in grass huts, hunting game with sharpened sticks and playing games along the banks of a river surrounded by desert sagebrush requires a much greater stretch of the imagination.

From oral histories, historical records and motion pictures I have some sense of what the Depression was like or how it felt to be traveling in a wagon train across the Oregon Trail, but little in my background relates to the nomadic lifestyles of the ancient Great Basin cultures that inhabited eastern Oregon, southern Idaho and northern Nevada for more than 10,000 years.

Who were these people? What brought them to this arid region and compelled them to stay, however briefly, at one location rather than another? How did they keep themselves fed, raise their children, get along with each other and improve themselves? How did they make sense of the world around them? What did they believe?

No one knows, for sure, even though their presence here is marked in stone.

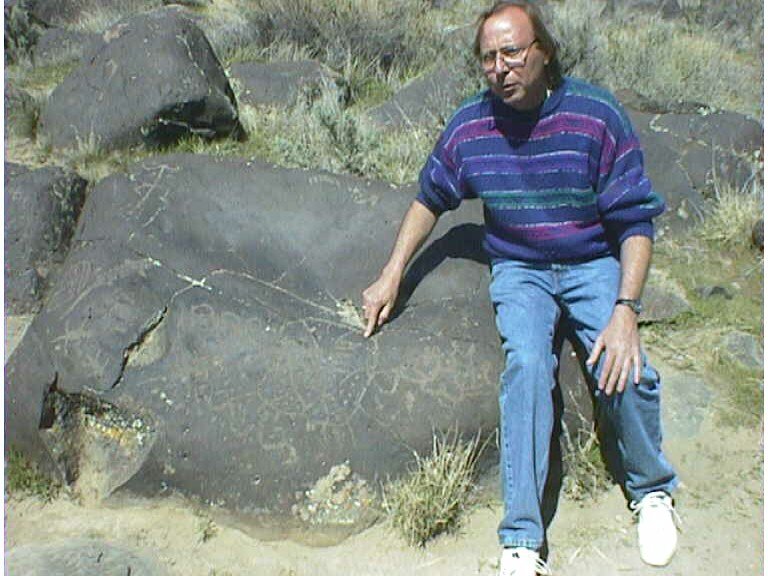

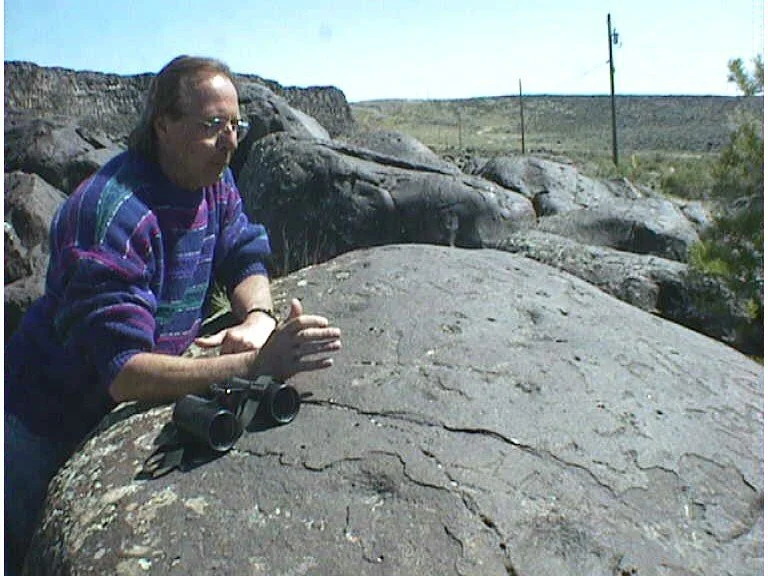

On the north side of the Snake River in southwestern Idaho, not far from a little town called Melba, lies a field of basalt boulders not unlike those found all across the inland Northwest -- remnants of volcanic cataclysms and great floods from eons past. Like most other modern-day visitors to this remote and seemingly desolate location, I would have walked past these commonplace chunks of black rock without a second glance were it not for Tom Bicak, the recreation planner who instigated Celebration Park in Canyon County.

But once I paused and took a second look at these rocks from a different angle, textures I first dismissed as lichens or pockets of erosion suddenly emerged in well-defined patterns, shapes and repeated motifs that no natural force would have created. Obviously the work of humans and obviously very, very old, the rock etchings -- or petrogylphs -- began popping out of the boulder field right and left, almost everywhere you looked, like an army that suddenly dropped its camouflage.

The semi-circles and wavy lines and comb-like forms that decorate these rocks date back as far as 9,000 years. Some are just a couple hundred years old, others have been baking in the sun for many a millenium. Sometimes the etchings of very different eras and very different peoples share the same boulder, as if Mark Twain had penned a tall tale on Moses' tablets.

But what these shapes mean, and who the artists were who made them, is lost in antiquity.

When Bicak began urging state and county officials to protect the petroglyphs and their boulder field as an archaeological district in the 1980s, only a few local fishermen and high school kids were familiar with the location. The site and petroglyphs were being vandalized and private collectors were carting off some of its treasures. The formation of Celebration Park, a 16-acre recreation area, put an end to the damage and developed the area for public use and education.

Although difficult to find (ask for directions when you get to Melba), the park is equipped with a visitor's center, camping sites, a native plants arboretum, hiking trails and an atlatl target range. The atlatl is the clever wooden throwing tool that archaeologists believe late Ice Age men used to hunt down wooly mammoths and other large mammals of their era.

Just like the nomads who made this one of their winter campsites for thousands of years, many of today's visitors come for the fishing or the Snake River's waterfowl. Eagles and hawks still nest and soar from the cliffs above, much as they have for eons, and rabbits still scurry for cover in the greasewood and sage.

But much has changed, as well, in the 12,000 years since humans first arrived in this canyon. Gone are the mammoths, sloths, saber-toothed tigers and wild horses that once roamed these hills. Gone too are the migrating salmon that once filled the river from shore to shore. Today's visitors arrive in pickup trucks and buses and family vans wearing fibers and carrying tools crafted in far-off lands. We picnic on deli-sliced, gourmet sandwiches and sip sodas from aluminum cans and try to comprehend people who slept in grass huts, hunted game with sticks and stones, carried their worldly goods in willow baskets and carved curious shapes in basalt boulders.

The artists who left their marks at Celebration Park -- at least 2,000 individual etchings -- certainly had something to say, and worked hard to make their statement. But what they had in mind is beyond my imagination.

Michael Hofferber © 1997 All rights reserved.