The fruit orchards of the Northwest are a seasonal home to a little-known subculture of migratory workers known as the "Okies" -- a mixture of people whose parents and grandparents left Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri and Texas during the 1930s to follow the crops.

The Dust Bowl days of the Great Depression that prompted their first migration are a distant memory, but many Okies remained in the fruit fields 50 years later, pursuing a peripatetic lifestyle by choice that their grandparents followed out of necessity.

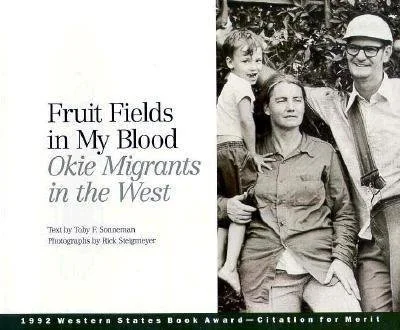

Author Toby Sonneman and her husband, photographer Rick Steigmeyer, discovered the Okies 20 years ago when they abandoned their unsatisfying city lives and took jobs as itinerant fruit pickers in central Washington. They spent a half dozen years on the "fruit run," traveling back and forth across the country from orchard to orchard, all the while keeping a record of their experiences in words and pictures.

"For all the hardships -- low pay, low status, back-breaking work, and often poor conditions in the field and inadequate housing -- most of the people who work in the fields and the orchards are not downtrodden, beaten individuals," Sonneman writes.

Her text emphasizes the self-esteem of individuals and the cohesiveness of a community that mainstream society failed to recognize.

"Although they are regarded with disdain and encouraged by schools, communities, and government organizations to leave agricultural work rather than to improve it, these people have miraculously clung to their self-repsect, believing in the dignity and value of their work. A sense of pride sustains them."

Steigmeyer's black-and-white photos -- mostly from the 1970s -- aptly illustrate this viewpoint. His intimate portraits and slice-of-life pictures of migrant camps, bosses, children and orchards portray an earthy, hard-working and close-knit people.

"Since the Great Depression little has been heard of the Okie migrants. They are considered extinct, as if all the poor white southern migrants had been absorbed into America's melting pot," writes Sonneman, who grew up as a Jewish high school student on Chicago's South Side.

"Cultural assumptions of an educated, middle-class society have often prevented Okie migrants from being understood or visible beyond the images from the Great Depression. Yet many Okies have remained in agricultural work by choice rather than by economic bondage, carving a unique niche in the history of agricultural labor."

"Fruit Fields in My Blood," which won the 1992 Western States Book Awards for creative nonfiction, follows the annual summer migration of pickers from the cherry orcards of central California to the Tri Cities, Wenatchee and Flathead Lake in Montana. Come fall, they harvest plums, pears and apples in Wenatchee and Cashmere. And in winter many go south to Florida to pick citrus.

Sonneman describes the work of fruit picking in these places and gives voice to the Okies' beliefs and concerns. Their judgments can be brutally honest or hardened with bitterness. A picker who made the long trek from Wenatchee to Montana only to find the cherries at Flathead Lake ruined by rain told Sonneman, "Well, it usta be we'd come up here and they'd just guarantee us a place to stay and two, three hundred dollars even if the cherries was all busted, just so a guy didn't lose nothin'. But now you know they got these Meskins workin' out there and they stopped doin' that."

Another picker agreed: "People can go out there and work for years and years for the same farmers and be just as loyal as they can about picking his good and his bad, workin' for whatever price he wants to pay and everything, thinking that he'll treat them right, and then all of a sudden you got out there one year and he's got all wetbacks out there, tellin' you he don't need you anymore."

This over-supply of labor that leads to lower piece-rates has driven most of the modern-day Okies from the fruit fields, according to Sonneman. She also blames child labor laws that prohibit families from working together and higher gas prices that make the migratory life less profitable.

The Okie lifestyle may be nearing its final harvest. If so, Sonneman and Steigmeyer may have come along just in time to collect the ripe fruits of a poorly appreciated people.