The developing nervous system makes far more nerve cells than are needed to ensure target organs and tissues are properly connected to the nervous system. As nerves connect to target organs, they somehow compete with each other, resulting in some living and some dying. Now, using a combination of computer modeling and molecular biology, neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins have discovered how the target tissue helps newly connected peripheral nerve cells strengthen their connections and kill neighboring nerves.

A report on the discovery -- A Model for Neuronal Competition During Development -- was published in the journal Science.

"It was hard to imagine how this competition happens, because the signal that leads cells to their targets also is responsible for keeping them alive, which begs the question: How do half of them die?" says David Ginty, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience and investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

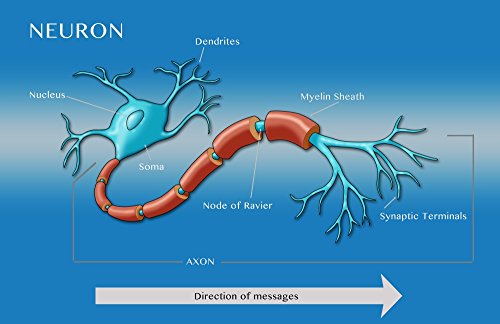

Target tissues innervated by so-called peripheral neurons coax nerves to grow toward them by releasing nerve growth factor protein, or NGF. Once the nerve reaches its target, NGF changes from a growth cue to a survival factor. In fact, when some populations of nerve cells are deprived of NGF they die. To further investigate how this NGF-dependent survival effect works, the researchers looked for genes that are turned on by NGF in developing nerve cells.

They found hundreds of genes that respond to NGF genes, some of which are involved in enhancing NGF's effect. With the observation that NGF seems to control genes that improve NGF effectiveness, Ginty's team hypothesized that this could be the way in which nerve cells compete with one another for survival. To test this idea the team turned to colleagues at the Krieger Mind/Brain Institute at Johns Hopkins who specialize in computer modeling of such problems.

The computer model they built assigns each nerve cell its own mathematical equation that take into account how much NGF the cell encounters or how effective NGF can be to simulate a cell's drive to survive. When they plugged in the model, it showed that over time -- about 100 days or so -- about half of the cells manage to survive, while the other half die.

But, in the developing mouse embryo, nerve cells that die do so over the course of two to three days just before birth. "We considered whether these nerves compete like other systems in the body, where those with stronger connections punish the weaker ones," says Ginty. The team turned their attention to other genes they found to be NGF dependent; two of which code for proteins that kill neighboring nerve cells and another is the receptor for these death proteins.

According to Ginty, nerves that connect to muscles undergo a similar process called synapse elimination where stronger connections stay connected and weaker ones are eliminated. The team wondered if this is also true of peripheral nerve cells competing for NGF availability and ultimate cell survival. To test this idea they plugged these three additional genes into their computer model, assuming that the stronger connected nerve cell punishes its neighbors by releasing the two proteins capable of killing. The computer model showed, once again, that half the nerve cells die over time, but this time the death occurred over two to three days rather than 100 days, just as in living animals.

To confirm that the model is accurate, the team went back to genetically altered mice. They predicted that removal of the punishment signals should delay cell death as observed in their early computer simulations. Indeed, nerve cells in mice lacking the receptor protein for the death signals died much slower than in mice with the receptor protein intact.

"I never would have believed that these three genes could speed up competition so much," says Ginty. "But there it was in front of us. It was amazing."

Source: Johns Hopkins Medicine