From Olympic snowboarders and World Cup soccer players to Academy Award-winning filmmakers and rock stars, women in American sports and entertainment can trace the source of their opportunities to a modest 5-foot-tall daughter of a widowed woman in rural Ohio who had knack for shooting a rifle and to a long-haired, goateed Army veteran.

Just a little over a century ago it was Annie Oakley (a.k.a. Phoebe Ann Mosey) and "Buffalo" Bill Cody who breached the stiff cultural barriers against women bearing arms or holding jobs or even participating in sports.

Oakley was not the first woman in America to shoot a rifle, but she was the first to do it publicly and effectively in competition with men, and she was the first to get paid for it handsomely.

Cody was not alone in his convictions that women should have the right to vote, be able to form their own organizations, to live alone without restrictions, and enjoy the same opportunities and pay as men. But he was the first American of the 19th century to act on those convictions on a broadly popular national stage, hiring some of the most talented horsewomen, rifle shots, and actresses in the country to work in his touring Wild West Shows.

"What we want to do is give our women even more liberty than they have," Cody said. "Let them do any kind of work that they see fit, and if they do it as well as men, give them the same pay."

Oakley almost missed her appointment with destiny, however. When she auditioned for the Wild West Show in 1884, she was turned down. Buffalo Bill and company already had a shooting act -- the well-known Captain A.H. Bogardus -- and didn't feel they needed her. But when Bogardus left the show unexpectedly the next year, Oakley was given a second audition and offered a job.

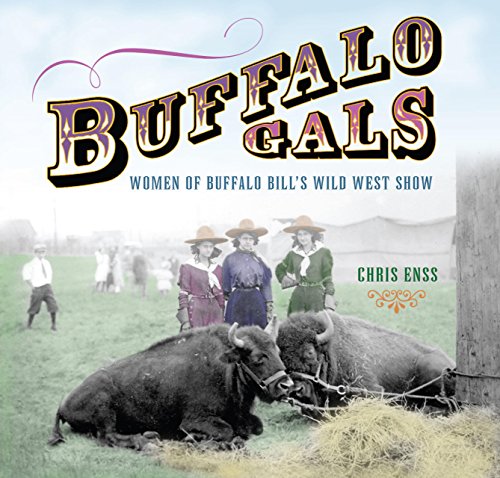

Oakley's opportunity, and subsequent success, opened the doors for other women entertainers in the Wild West Show -- Lillian Smith, Della Ferrell, Georgia Duffy -- and demonstrated that the Wild West of America's frontier mythology was not an exclusively male story.

"Young women admired these cowgirls -- women who dared to break out of society's traditional roles, jump aboard a horse, and hold their own in a predominantly male profession," writes Chris Enss in "Buffalo Gals: Women of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show" (TwoDot, 2006).

Oakley's most impressive accomplishment, according to some male historians, was her ability to compete and excel without losing her feminine identity. "Most Americans view expertise with firearms as a male role," says Paul Reddin in his history, "Wild West Shows" (University of Illinois Press, 1999). "Yet this woman displayed obvious ability while remaining conventionally feminine, always making her entrance a 'pretty one.'"

A publicity agent once said of Annie Oakley: "She never walked. She tripped in (to the arena), bowing, waving, and wafting kisses."

A "girlie girl" competing in a "manly" sport or profession and succeeding was much more astonishing in the 1880s than it is today, evidence that something has changed and that the retorts of a poor country girl from Ohio are still echoing out of the past.

"Aim at a high mark and you will hit it," Oakley advised women with ambitions. "No, not the first time, nor the second and maybe not the third. But keep on aiming and keep on shooting for only practice will make you perfect. Finally, you'll hit the Bull's-Eye of Success."